Down the Rabbit Hole

The perils of sports betting

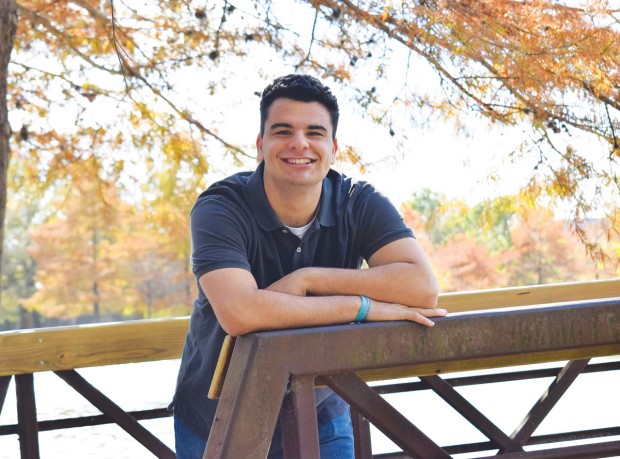

Saul Malek sits in a Houston coffee shop, twiddling a straw wrapper between thumb and forefinger, recalling an activity that jolted his senses into sharp focus as a child.

Putting a coin to a scratch-off ticket.

Saul and his fraternal twin brother looked forward to the innocent scratch-off treats, inserted into their birthday cards occasionally. His brother would make a few swipes, then toss. No win, no biggie. Saul, on the other hand, maneuvered coin to ticket like a tactical surgeon, skillfully peeling away every speck of its coating. Clearing margins. Double-checking for surprises.

“I’d swipe it clean. It makes me think I had certain tendencies even way back then,” says the 25-year-old Trinity University graduate, who grew up in West University Place. “I remember finding 10 bucks on the playground in first grade and celebrating that. My teacher made me turn it in to Lost and Found. I wonder if, in some odd way, I was chasing those 10 dollars from all those years back.”

Today, Saul is a recovering sports betting addict. Over four years clean. “Since July 18, 2019,” he announces, hands plowing through a head of thick, black hair.

The young, the vulnerable, they’re just clicks away from an addiction with serious consequences, he stresses. They have a casino in their pocket. Their smartphones. A gateway to sports betting apps.

“There’s a lot of peer pressure for kids about betting. I imagine a kid would feel ostracized watching the Super Bowl with friends if everyone had action and you didn’t. It’s like if everyone’s playing beer pong and you’re sitting there in the corner drinking a bottle of water.

“A lot of parents don’t even have it on their radar,” explains Saul, whose addiction led to lying, cheating, and manipulating people to support his urge for non-stop action.

“It’s a deep hole. You don’t want to fall in.”

SOBERING STATISTICS There has been a 30-percent uptick in sports betting addictions over the past few years. Males, typically ages 18-24, are the most affected group. Many seek help by their late 20s to early 30s, once they’ve experienced consequences. (Photo: www.istockphoto.com/simonapilolla)

The gambling landscape has changed dramatically and quickly with the advent of new technologies and a 2018 landmark Supreme Court decision that allowed states to make sports betting legal within their boundaries.

While sports betting is illegal in Texas, there are ways around the regulations that include the use of offshore betting websites or a VPN (virtual private network) that can be assigned to U.S. states where betting is illegal. And there are traditional bookies that don’t use online betting tools.

And with all these changes comes a different kind of gambler. “We aren’t talking about the old-timers going to the racetrack in Yonkers in the 1980s anymore,” says Saul. Mobile access to sports betting is like never before, a forum for a throng of young people.

Between 60-80 percent of high schoolers say they've gambled for money in the past year, and up to 6 percent are addicted to betting, according to a 2022 study by the International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviors.

Never mind that teens and young adults have immature brains. Literally. The decision-making prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning, prioritizing, and making good decisions isn’t fully developed until the mid-to-late 20s, say experts.

Saul can relate. He recalls blundered choices in high school that set the foundation for a serious sports betting addiction.

He’d play the game Big Win Sports on his iPad at St. John’s School instead of taking notes in class. Its website encouraged purchases in exchange for “big bucks” credit to play the game.

“I’d google ‘fake credit card generator’ and use some number that fits the algorithm but wasn’t a real person’s credit card. So, I’d use those credit card numbers and make up some random address and then have cakes I’d purchase on their website sent to random prisons, stuff like that. Then I’d be awarded this credit so I could play the game at a higher level.

“I remember thinking I was really smart for a high schooler,” he continues. He scammed another game called Big Fish Casino regularly. “I’d have a million chips through these fake accounts I’d made. Eventually it got so bad that people in the Big Fish Casino Facebook page would say ‘There’s a scammer going around.’ And yeah, that was me.”

By his senior year of high school, he indulged in the fantasy sports app DraftKings, creating daily lineups on his cell phone with a fictional budget, putting down real money to enter head-to-head competitions and tournaments.

Then came college, a whole other ball game.

He recalls winning a bet and receiving $1,992 in cash in his dorm mailbox. “I took it to class and flashed all these 100-dollar bills on my desk before class started. I thought I was a bigshot.”

Mostly, he gambled on credit with money he didn’t have. He’d find an online sports book, sometimes winning enough to pay a former bookie back. But most times he lost. Then he would block the bookie’s number, find a new sports book, and repeat the cycle.

A CLICK AWAY Smartphones, with their sports betting apps, are the new casino, making sports betting more available than ever. Between 60 to 80 percent of high schoolers say they’ve gambled for money, and 6 percent admit addictions, according to a 2022 study by the International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviors. (Photo: www.shutterstock.com/Wpadington)

His parents bailed him out for hundreds of dollars several times. “In college, they realized I had a big problem. I asked them directly for help because I owed this guy money, and I didn’t have it. They were upset and worried, but at the same time thought, ‘Ok, we will do it, and then you pay us back.’ Because they would rather have themselves as the person I owed money to, than some stranger coming after me.”

But addictions cling like a python to prey.

“I was in its clutches. If one of my debts was cleared, I felt like I had a free victory. So, I lied to my parents that I was finished, but I wasn’t.

“It’s hard to explain the rush,” he explains. “It’s a dopamine hit. It’s about the action more than anything. At first, I was really preoccupied about whether I won or lost, but then it didn’t matter. It was just about getting the next bet, getting the next fix. And you want to be able to stop after you’re addicted, but there’s no amount of willpower to deny that compulsion.”

In August 2018, Saul went to his first 12-step meeting, at his parents’ urging. “For the first month, I was like a dry drunk. I wasn’t betting, but nothing had changed.” Then his sponsor gave him some sober advice: You’ve got no shot at any long-term sobriety if you don’t start working on your character and get serious. It’s a life-or-death situation.

“I’ve been going to my meetings ever since and really working on myself. He told me that recovery from gambling isn’t entirely about placing bets. It’s about not having a risky lifestyle, making better choices, and trusting a higher power. I don’t have any desire or urge to gamble anymore,” says Saul, who is pursuing speaking engagements at schools and various organizations to warn young people about the perils of sports betting.

He's trying to make it right, chipping away at his debt, paying people he owes. Clocking in hours as a driver for the ride-hailing service, Alto, in Dallas.

He whips out a paper from his pocket, his journal of accountability.

“It says here I still owe about $5,000, and that’s just to people I’m making payments to. I’d say it’s closer to $8,000 to $10,000 because I still technically owe my parents back money they used to bail me out, and online loans I ended up taking out. And then there’s some bookie I couldn’t contact, and I owed him like a thousand. I made the effort. One day I might donate that money to charity to make good on it.”

Therapist Dalanna Burris, Behavioral Addictions Specialist at The Menninger Clinic, is all too familiar with such chronicles of sports betting. She hears stories like Saul's through her own patients. She cites a 30 percent increase in such addictions over the past few years, typically males, ages 18-24.

A gambling disorder is diagnosed typically in the late 20s, early 30s when they’ve experienced consequences. “They may have been betting for years but were able to skirt consequences due to being in college and parents helping them out more,” she explains.

The pandemic lock-down didn’t help, says Burris, who gave a talk on the evolution of betting at the Texas Association of Addiction Professionals’ annual conference in San Antonio. “I think it was a perfect storm between Covid and all these apps being developed and all the regulations decreasing about gambling. It is really impacting our next generation of young men. A very high percent of adolescents, 12 to 17 years old, have begun betting because of the availability of these apps.”

The addiction carries a high suicide rate. “One out of five people with a gambling disorder have either attempted or contemplated suicide,” she says.

“I think that parents aren’t aware of the availability of gambling. And kids will sometimes use a coin base to exchange funds without using real money. It’s a secure online platform for the transfer of cryptocurrency and most parents don’t have a clue about it.”

It’s important that parents talk with their children about today’s gambling landscape, Burris adds.

“Parents in general should encourage their children to be curious about how they manage uncomfortable emotions or build excitement. And I advise parents to discuss openly with their children their state’s laws and regulations regarding gambling. If they have children or young adults who enjoy sports, specifically discuss the consequences of problematic gambling,” she stresses. “Youth may not initially listen to their parents, but this will lay a foundation of conversation for the future should that conversation be necessary.”

Burris uses a whiteboard in her office to go over basic rent, income, a budget, with patients so they can get a realistic vision of money. Holding actual cash in their hands is part of her treatment. “If you hand people 20 bucks, whoever has a gambling disorder looks at that $20 and sees the potential of $200, or $2,000. So, budgeting becomes a large pillar of their treatment, bringing people down from this fantasy.”

“In the course of a year, I probably lost around $35,000 to $40,000,” says one of Burris’s patients, a Tanglewood resident, 31, who asked to remain anonymous. “Up until 2019, when I started sports gambling, I had never gambled. No type at all, in my life.”

Like Saul, he didn’t think he had a problem. After all, ads were everywhere, commercials airing with sporting events, imploring folks to “put some skin in the game.” Podcasts dwelled on sports betting, the odds.

The Rockets were his preferred team to bet on in the beginning, and his confidence soared early on when he hit a big parlay, winning $900. Beginner’s luck. He started betting on more teams in the NBA. When Covid hit and games were cancelled, his need for gambling had him betting on soccer in the Republic of Belarus in Eastern Europe. When American sports returned post- pandemic, he needed instant gratification, switching to NBA video games that could decide in minutes if he’d won $20 or not.

“That’s when I knew I had a problem. I threw away strategy for instant gratification. The feeling of winning became less and less fulfilling and the feeling of losing got worse and worse.

“I had a pretty major addiction to marijuana, too,” he says, of a rehab stint where he met Burris. He lost his job at a non-profit due to his addictions. He opened up about his gambling problem during treatment.

“There are a lot of cross addictions,” he says. “Dalanna taught me a lot. I learned so much. To be honest, I was much more embarrassed about the betting addiction than the weed.

“There are a lot of things she said that resonated with me,” he continues. “I have an addiction towards fantasy. So, for sports gambling, she told me that some people imagine themselves in the game. That hit home because, as a kid growing up, a lot of my fantasies were about becoming an NBA player. That’s what really drew me in the beginning.”

He’s happy to be clean of his gambling addiction, for 10 months now. And he once again has a healthy relationship with sports. “My mom played Olympic basketball for Syria. I’m close to my mom. And the Rockets were my team. I missed watching games with her. Now there’s no urge to gamble. There used to be a time I couldn’t be on my phone when watching because she was worried I was gambling. She doesn’t have to worry about that anymore.”

Parents shouldn’t be so naïve as to think their children are “too good for that,” he adds. “It’s everywhere now. People at work do it, people at school do it. Watch sports but put your phones aside. Make it a family activity where your kids develop a sentimental connection, an emotional connection to a sport they love. Then they can overcome any pull to gamble.

“Otherwise, they could literally get to the point where they’re betting on soccer in Belarus.”

Editor’s note: To book Saul Malek for speaking engagement services, visit: saulmalek.com

Sports Betting

Identifying the Signs

A sports betting problem can be hidden and hard to identify at first, say experts. Be aware of sharp mood swings, and an inordinate amount of time spent on sports apps, obsessions with sports scores, stealing and lying about it, having unusual amounts of cash with no reasonable explanation, receiving phone calls from strangers, and selling of personal possessions.

Parents should also be on the watch for cryptocurrency that is used to hide online betting activity. The anonymity offered by cryptocurrency transactions provides an increased level of privacy, which is particularly appealing to younger individuals who may not have access to traditional payment methods or desire to conceal their gambling activities.

Getting Help

The National Problem Gambling Hotline (1-800-522-4700) is available 24/7 and is 100 percent confidential. This hotline connects callers to local health and government organizations that can assist with their gambling addiction.

National Council on Problem Gambling: ncpgambling.org/programs-resources/resources

Gamblers Anonymous: gamblersanonymous.org/ga/index.php

Cambridge Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School’s Toolkit for Gambling Disorder: divisiononaddiction.org/outreach-resources/gdsd/toolkit/information

Evergreen Council on Problem Gambling: evergreencpg.org/awareness/resources-and-downloads

Gam-Anon: gam-anon.org

The Menninger Clinic: menningerclinic.org/treatment/treatment-for-adults/inpatient-programs/addictions-services-adults or 713-589-5860.

Want more buzz like this? Sign up for our Morning Buzz emails.

To leave a comment, please log in or create an account with The Buzz Magazines, Disqus, Facebook, or Twitter. Or you may post as a guest.